This content is for Premium Subscribers only. To view this content, login below or subscribe as a Premium Subscriber.

Related News Articles

EGC and Trafigura Ship Copper and Cobalt to Global Markets via the Lobito Atlantic Railway

13 February 2026

SADC, Angola

1 min

Zambia, DRC and Angola Align to Accelerate Lobito Corridor Implementation

05 February 2026

SADC, Zambia

2 min

Construction of the Luena–Saurimo Railway Branch Line Officially Launched

30 January 2026

SADC, Angola

3 min

Namibia and Angola Establish Railway Joint Technical Committee

23 January 2026

SADC, Namibia

2 min

Lobito Atlantic Railway Secures USD753 Million to Accelerate Development in Angola

18 December 2025

SADC, Zambia

1 min

Angola Launches Tender for Namibe Corridor Railway Concession

05 December 2025

SADC, Angola

1 min

EU Expands Engagement in the Lobito Corridor under Global Gateway Initiative

14 November 2025

SADC, Zambia

2 min

U.S. EXIM Debt Funding to Accelerate U.S. Mine-to-Magnet Supply Chain

03 November 2025

SADC, Angola

3 min

CFB, LAR and Partners Launch Rail Safety Week 2025

10 October 2025

SADC, Angola

1 min

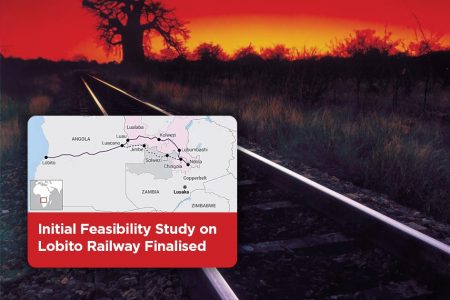

Initial Feasibility Study on Lobito Railway Finalised

29 September 2025

SADC, Zambia

2 min

Integrated Moçâmedes Bay Development Project Set for October 2025 Opening

29 September 2025

SADC, Angola

1 min

LAR Strengthens Governance with New CEO Appointment and Board Leadership

24 August 2025

SADC, Zimbabwe

2 min

2 min